Traditionally investments such as government bonds have been considered “safe”, whereas shares are considered “risky”.

So pervasive has this been, that, in the jargon of financial markets, when somebody talks about “taking on more risk”, what they are really saying is that they are selling bonds and buying shares (or using cash to buy shares). Conversely, if they are selling shares and moving to bonds or cash, they are “reducing risk”.

Now, it seems, the jargon is moving mainstream. I recently saw a retiree being interviewed on television. In order to make ends meet, he said he was “taking on more risk” with his investments.

How suitable is this system of risk classification in the current environment?

I argue that it is not suitable at all, and it is time to reassess what is risky, and what is not. Consider the following:

• Most of the research into the performance of bonds and shares has occurred in conditions very different from what we now have. Interest rates now are at record lows, and in some countries even negative (which theory said was impossible).

• The relative “riskiness” is based on one measure only – the volatility of total returns (growth and income) of bonds and shares.

• Volatility consists of both decreases and increases in returns. This is a method favoured by academia, but I have yet to meet anybody in the real world who regards them as the same.

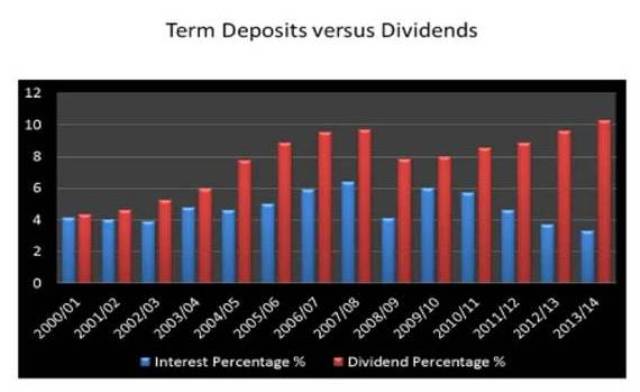

• However, when we break the returns down into their two components (income and growth), we see that income from shares is far less volatile than income from bonds, when taken across the whole market.

• With interest rates so low, there is a substantial risk of big capital losses from bonds, if rates rise.

• Over the longer term, there has been a strong historical trend for income from shares to rise (across the whole market), whereas interest rates are all over the place, rising in some years and falling in others.

• Also over the longer term, there has been a well established tendency for the value of shares to rise. Not so for bonds and cash.

• If somebody is drawing 5% (the minimum allowable between ages 65 and 74) from their account based pension, then their balance is certain to fall if the money is in “safe” term deposits. With rates of around 3.25% (on a good day), that equates to a shortfall of 1.75% pa even before we talk about other expenses. In this case, you are sure to see your account balance going backwards. That looks pretty risky to me.

In a recent client newsletter, I tracked the position of two amounts invested in 2001. Both amounts were $100,000. One was invested in 12 month term deposits, with the capital being reinvested each year, and the interest used for living expenses.

The other $100,000 was invested in a portfolio of shares, and the income was spent each year.